Newman and His Critics,

by Edward Short – (Gracewing, £35.00 pb / £65.00 hb)

This large and very detailed book, running to some 600 pages, is one of three which the author has written on John Henry Newman.

He has already published Newman and His Contemporaries and Newman and His Family. Those earlier volumes are now again available to make a matching set with this new, but delayed book.

This way of treating his subject is a wise one. Speaking from experience, one of the difficulties a biographer has in writing about the subject’s life is how to deal with intellectual developments, conflicts and controversies. These topics require space to develop properly, but they hold up the ever forward drive of the biographical narrative, and can in the opinion of some readers, clog the narrative.

Short’s method in this book is to take a set of six critics spread over the course of Newman’s life, from his Anglican days down to Wilfrid Ward and the notable Ian Kerr, to whose biography the admirers of Newman owe so much.

(All writers on Newman owe an even greater debt to the gentle but unremitting Fr Charles Dessain, who laboured so long and so thoroughly over the many volumes of the Catholic series of the Letters and Diaries.)

Discourse

By critics he means those who entered into intellectual discourse with Newman in an attempt to understand his ideas, and perhaps to help him to by debate, to refine them. But it has to be admitted that Newman had his enemies, as the Achilli case of 1851, which so deeply affected him, revealed.

One of the most penetrating chapters in this book is Short’s account of the passage of arms between Newman and Charles Kingsley. This had one great outcome: it influenced Newman to set down in writing his religious life in the pages of his Apologia Pro Vita Sua.

Short gives a measured and detailed treatment of this unhappy episode from which Newman emerged triumphant. Kingsley’s attitude is difficult to appraise; but Short surely misses one angle at least, in giving no consideration to Kingsley novel Westward-Ho (1855) , which gives a clear picture of just what Kingsley thought about the cruelties of the Spanish and the beliefs of the Catholic Church.

All too often admirers of Newman seem content to see him in the more confined world of Catholic life, rather than as the major figure of his era that he really was”

This would have provided an opportunity for Short to take Neman beyond the world of Catholic opinion into a wider field. When it appeared Apologia pro vita Sua took its place at once among the great works of English Victorian literature, a book to be discussed and appreciated in the context of Ruskin, and Matthew Arnold, and others. All too often admirers of Newman seem content to see him in the more confined world of Catholic life, rather than as the major figure of his era that he really was.

There is much to enjoy in these pages, especially what is said about Wilfrid Ward say, or about Ian Kerr.

It is, however, a disappointment to an Irish reader to find that Edward Short has not managed to build a chapter around Newman’s time in Ireland, a period when indeed he faced many critics, especially in the Irish hierarchy, about what he was attempting to do in Dublin.

He seems to have envisaged a “medieval university” for a liberal education on the model of Oxford, where the laity would be taught. The Irish bishops had in mind something more like a seminary which would educate candidates for the priesthood, modelled on Louvain. but not the children of the Catholic middle classes,.

There are references in the text, of course, to Dublin and to Irish people, but no orgnaised treatment of the whole episode. This is in keeping with what seems to be the current attitude among Newman admirers both in England and North America, to see Newman’s time in Ireland as an unfortunate aberration.

Curious

This is certainly curious, seeing as he left behind him a secondary school which still flourishes in the hands of the Marists, a university college which also continues, and also fine example exampled of Romanesque architecture in the University Church on St Stephen’s Green, that is one of the great masterpieces of our built heritage.

This book and its associated volumes will rightly find a place in even the smallest serious library of Newman books. They will be read for the light they shed, not only on Newman himself, but on those he was associated with, and many will be indebted to the author for his industrious and long sustained research and always readable understanding of Newman.

Peter Costello

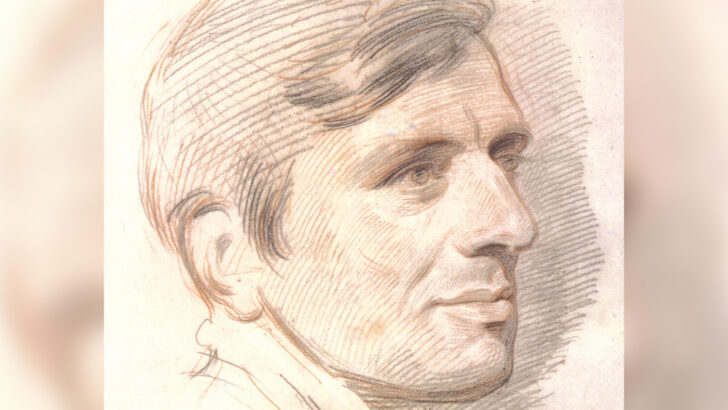

Peter Costello The younger John Henry Newman

The younger John Henry Newman